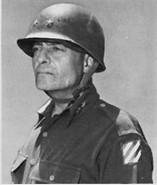

Lucian Truscott

Lt. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., Commander, Third Infantry Division, VI Corps, Fifth Army

born Jan 9, 1895 Chatfield, Texas

died Sep 12, 1965 Alexandria, Virginia

Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. came from a troubled family in rural Oklahoma. His mother was a college graduate and his father a physician. However, the family had to move often because of the father’s addiction to drugs and alcohol. Truscott got a job teaching high school at age 16, although it was not clear that he had ever graduated from high school.

He didn’t graduate from any college, let alone West Point. He joined the cavalry at age 22, was chosen for Officers Training Camp, commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant, and became a cavalry instructor. He did not serve in WWI and had never been to Europe. In 1934 then Captain Truscott was admitted to the Army Command and General Staff school at Ft. Leavenworth. After graduating in 1936, now Major Truscott stayed on for four more years as an instructor.

A quick study, Truscott in a short time became a cavalryman, horseman and world-class polo player, instructor, statesman, diplomat, master strategist, innovator, and author. He got ahead because of his honesty, perseverance, an analytical mind, a knack for problem-solving, leadership qualities, modesty, and a well-balanced personality. He made trusting friendships along the way, and impressed all the top Army brass he met, including generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, George C. Marshall, George S. Patton III, and Mark W. Clark. The superior leadership qualities of Truscott in this article stem in large part from Patton’s diagnosis with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), and Clark, not fully diagnosed, but also exhibiting many narcissistic qualities. NPD leads to grandiosity, vanity, social climbing, craving attention, exhibitionism, sense of entitlement, exploitation of others, lack of empathy, envy, racism, and snobbishness.

A quick study, Truscott in a short time became a cavalryman, horseman and world-class polo player, instructor, statesman, diplomat, master strategist, innovator, and author. He got ahead because of his honesty, perseverance, an analytical mind, a knack for problem-solving, leadership qualities, modesty, and a well-balanced personality. He made trusting friendships along the way, and impressed all the top Army brass he met, including generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, George C. Marshall, George S. Patton III, and Mark W. Clark. The superior leadership qualities of Truscott in this article stem in large part from Patton’s diagnosis with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), and Clark, not fully diagnosed, but also exhibiting many narcissistic qualities. NPD leads to grandiosity, vanity, social climbing, craving attention, exhibitionism, sense of entitlement, exploitation of others, lack of empathy, envy, racism, and snobbishness.

At the beginning of WWII Truscott was among the first to go to England for planning, and learned how to get along with and benefit from the British. Inspired by British Commandos, Truscott was the founder of the American Rangers, including the famous Darby’s Rangers. He also trained his men in the 3rd Infantry Division to a new standard of physical fitness, enabling them to run five miles the first hour and four miles per hour thereafter wearing full battle packs (the “Truscott Trot”).

Patton and Clark, the Showmen. Neither Patton nor Clark got along well with the Brits. While Patton disdained staff work and staff officers like Eisenhower, Truscott fully embraced them. He understood that rehearsals and careful planning would save many lives, and became a master of logistics. While he almost always obeyed orders — even those with which he disagreed, he did not hesitate to forcefully voice his objections to first try and modify or squelch the orders.

Truscott took some of the dirtiest jobs the Army had to offer without complaint. Working under Patton in Sicily as 3rd Infantry commander, he fought his way to Palermo and Messina, and each time waited for Patton to arrive and accept the glory. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) for valor during the invasion of Sicily.

Working under Clark in Italy first as 3rd division and later as VI Corps commander, he fought his way through Anzio to Rome and Bologna, and each time waited for Clark to arrive and accept the glory. On Anzio beach, Truscott lived above ground like all his men—close to death from constant bombardment and sniper fire for almost five months.

Truscott the Maestro. Truscott became one of our greatest experts on amphibious landings, which he put to good use in planning and commanding three American divisions in Operation Dragoon, the 50,000 man invasion of southern France on Aug. 15, 1944.

Patton’s vanity never allowed photographs of him wearing glasses, and he didn’t like his teeth to be photographed. He preferred a profile from the left side. Clark only allowed photographs of his left side. Patton wore the most expensive riding boots, which were always polished to a mirror-finish by his personal valet in order to impress people. Truscott also wore his riding boots, but mostly for good luck and protection in combat. With their ingrained mud and shrapnel scars, his boots were not intended to impress.

A master negotiator and arbitrator derived from an innate understanding of human character and psychology, Truscott learned during the war how to successfully command French, Philippine, Brazilian, Japanese-American, South African, Canadian, Italian, African-American, Indian, British, and U.S. mountain troops. Against protocol, he liked to do his own aerial reconnaissance, flying in a 2-seater P-51 Mustang fighter plane while it was sometimes engaged in strafing the enemy.

After the Normandy invasion, when the world’s attention was on Northern Europe, Truscott agreed to stay in Italy to finish the job of driving the Germans out. Never one to seek publicity or promotion, Truscott eventually replaced both of the showmen, Clark and Patton. In Dec., 1944, he took over as commander of the Fifth Army when Clark was promoted. In Oct., 1945, he took over the Third Army when Patton was removed for political blundering.

When WWII ended, Truscott was the commander of the Third Army and military governor of Bavaria. He successfully managed the complex and sensitive multicultural problems of feeding the populations, denazification, conducting war crimes trials, and repatriating the millions of prisoners and displaced persons. In 1954, retired from the Army, he was promoted to four star general, commensurate with his duties as 5th Army commander. He continued to work for the CIA during the Cold War and as an informal advisor to President Eisenhower.

Cartoonist Bill Mauldin, famous for pin-pricking inflated egos, was a thorn in Patton’s side. Truscott liked him and they became friends in Italy. Mauldin wrote, “Truscott was one of the really tough generals…[He] could have eaten a ham like Patton for breakfast any morning…Truscott spent half his time at the front–the real front–with nobody in attendance but a nervous Jeep driver and a worried aide.”

There is an American cemetery at Anzio containing some 20,000 graves. On Memorial Day, 1945, Truscott spoke at a ceremony attended by senior brass, congressmen, and other VIPs at the brand-new cemetery. Many of the fallen had been under Truscott’s command. As written in the biography by Harvey Ferguson,

The general, without speaking notes, walked to the microphone, acknowledged those seated before him, and turned his back. He faced the graves before him and spoke only to the fallen soldiers. In his distinctive gravelly voice, Truscott apologized that they were there and asked their forgiveness if any mistake by him had caused their deaths. He promised that he would never speak of the glorious dead because he saw no glory in having to die while still in your late teens or early twenties.

Instead of making the occasion about himself or American military might, Truscott was moved by the characteristic so lacking in narcissists—his empathy.

References:

Truscott, Lucian K. Command Missions. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1954.

Ferguson, Harvey. The Last Cavalryman: The Life of General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

“Patton’s Madness: The Dark Side of a Battlefield Genius,” by Jim Sudmeier, Stackpole Books, 2020.

[Truscott is the other person listed in My Heroes that I never met]